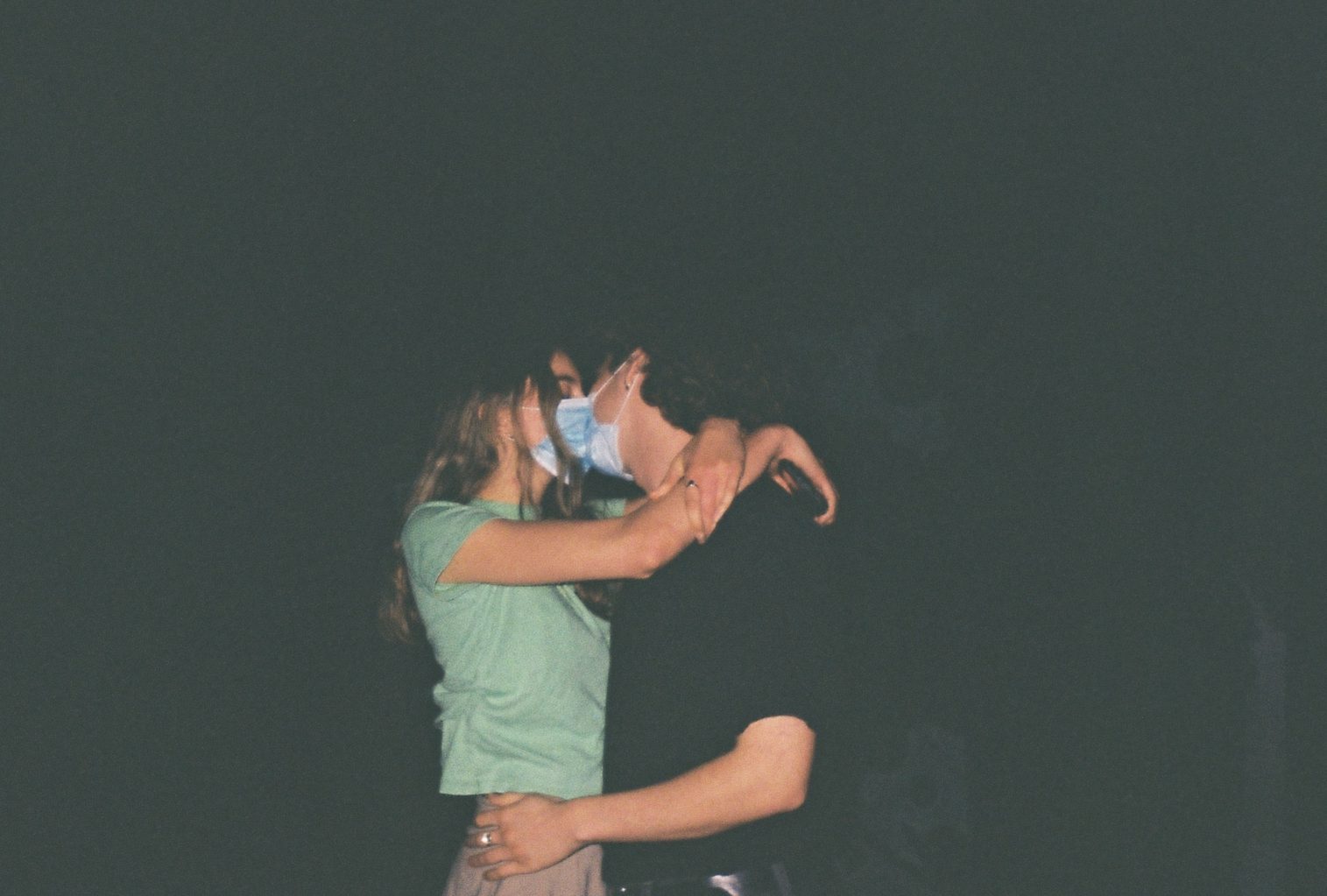

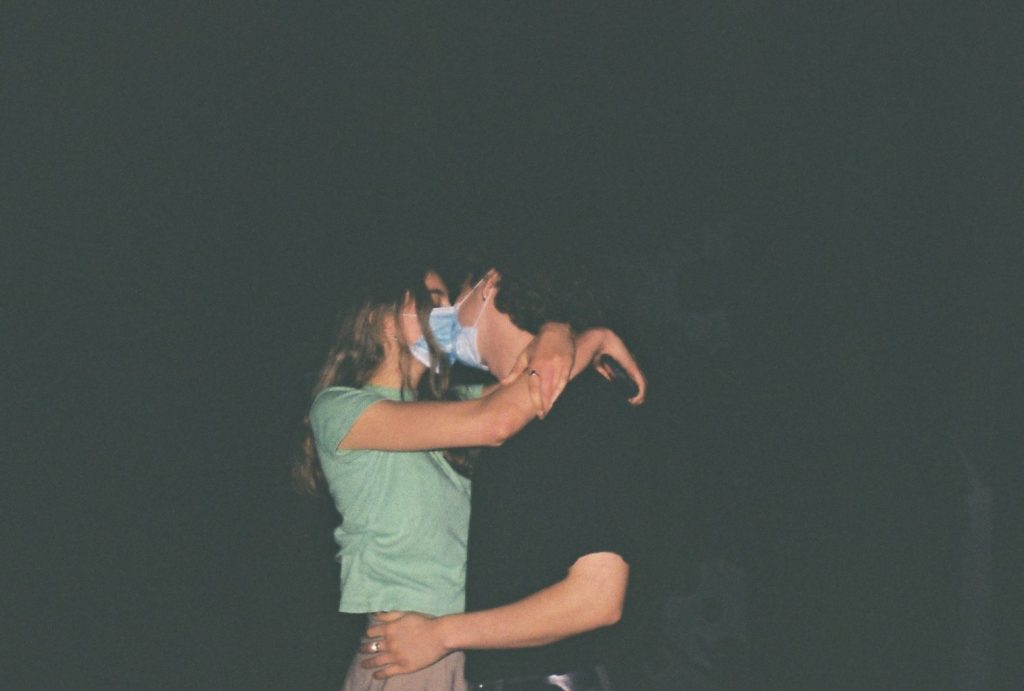

The unprecedented arrival of the Coronavirus Pandemic and its subsequent restrictions forced galleries worldwide to close their doors; yet rather than perishing in isolation galleries amalgamated with the digital realm. This article explores the plethora of ways in which galleries adapted to the digital realm, and what galleries can learn from their experiences in the virtual world.

As I write this article Melbourne is in the middle of another two-week snap lockdown, the fourth lockdown to affect Melbourne since March 2020. After only four months between this and the last lockdown, a pattern of opening and closing seems to be appearing- the community goes into a hard lockdown, the cases go away, the restrictions lift, and complacency arises. This pattern combined with the blatant shortcomings of the federal government’s vaccine roll out seem to suggest that these punctuations of restrictions and lockdowns will be a continuously affecting issue. And whilst these lockdowns have undoubtedly negatively affected a number of arenas, this essay will focus on how the pandemic accelerated the galleries entry to the digital realm and rank two Melbourne galleries approaches to digital collections: The Buxton Contemporary and the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV).

2. The National Gallery of Victoria

The National Gallery of Victoria followed in the footsteps of its European predecessors the British Museum and the Louvre through its digitisation of the physical museum space. Clunky, glitching and lacking nuance these virtual tours mirror an interactive story-based video game of the mid noughties. Controlled by clicks from a socially distanced computer, the viewer can guide themselves throughout curated virtual exhibitions. However, the experience is far from an embodiment of walking through the gallery as the 3-dimensional visualising program that the NGV uses, Matterport, only moves in a forward direction and does not allow for any pivoting. Whilst this linear method of movement can work well with two dimensional artworks like paintings, photographs and prints, this virtual reality technology does not afford itself to 3-dimensional artworks like sculptures and multi-medium installations.

These downfalls are clearly seen when observing sprawling artworks such as Alicja Kwade’s WeltenLinie, a multifaceted installation that uses double sided panes of mirror to create a sensitivity to space and perception. In the digital tour none of the artwork’s nuances comes through, the reflective mirror surface fades to another clear passageway and the whimsical explorative nature of this artwork are diluted.

In addition to the aesthetic downfalls of the virtual gallery, platforms like Matterport that create digital twin models are difficult to navigate and oftentimes you find yourself facing a wall with no way to turn around, frustrated and confused. This means that the viewer is constantly having to restart the exhibition which can become tedious and frustrating- not the experience the museum wants its visitors to have.

With all of the affordances of an established institution at the NGV’s disposal, their approach to the digitisation of their institution was bland and difficult to use. And whilst they did host a range of talks and event online alongside their virtual tours, they relied heavily on their virtual tours to support them.

1: The Buxton Contemporary Gallery

Compared to the digitisation of the NGV, The Buxton Contemporary approached their expatriation to the virtual world in a far more creative and inspired way. Rather than mirroring their physical collection in an online platform, the Buxton Contemporary worked in collaboration with six artists to create a series of six virtual site-specific artworks for their new project named Light Source Commissions.

Rather than artworks being unfairly relegated to digital platforms- as seen at the NGV- these six commissioned pieces were created with the affordances and possibilities of the virtual realm in mind.

Stuart Ringholt, a Melbourne based artist, was one of the people who participated in Light Source Commissions creating the humorous artwork Looking at the Painting Without Clothes on in the Safety of Your Own Home. Rather than using digital mediums like the five other participating artists, Ringholt used the Buxton Contemporary’s website as a tool for people to order artworks to their houses. Looking at the Painting Without Clothes on in the Safety of Your Own Home came as a flat packed painting and instructional booklet, it instructed viewers how to assemble the artwork and how to experience it. As stated in the title the work is to be viewed nude at home, allowing a complete and unique sensory experience that for many can only be achieved in the privacy of their own home.

These self-assembled artworks function as an internal meditation; no longer are you observing the nude- you are the nude. As an artwork that is part of a digital artistic program, Ringholt’s decision to focus on physicality and introspection is interesting. The other five artworks in the series all uses digital mediums such as film, artificial intelligence, virtual reality and digital collages to create their works

Whilst an inherently physical experience, the way in which Ringholt uses the internet to disperse his artworks free of charge, evokes memories the characteristics inherent to Web 2.0; the earliest iteration of the contemporary user-generated internet era, prior to its capitalisation. Looking at the Painting Without Clothes on in the Safety of Your Own Home embraces Web 2.0’s ideologies of user participation, collaboration and accessibility, encouraging the audience to use the internet as an instrument to achieve something.

Looking at the Painting Without Clothes on in the Safety of Your Own Home is ultimately a digital artwork as without its website and registration form it would not exist, nonetheless, as an artwork created during lockdown it understands the limitations of the digital. At a time where virtual platforms like zoom and Facebook messenger arose as the primary form of communication for friends, family, co-workers and schools, Ringholt understood the limitations of the digital and created a nuanced artwork that gave viewers an opportunity for quiet contemplation. It is this inherent meditative quality that makes this work so impactful.

It is this style of art that is imperative to inspiring engagement within the gallery during periods of lockdown. Virtual Tours, whilst good at showing off the entirety of the gallery’s collections, are disembodied and disengaged methods of digital curation. For the gallery to stay present in a time of physical distancing, innovative models of curation and engagement need to be explored- ones that utilise the affordances of isolation and digital mediums to their benefit rather than being swallowed up by the technology.

Leave a comment